New EPA PFAS Reporting Rule Covers Thousands of Products

PFAS, Newsletter Articles

Over the next 18 months, thousands of manufacturers and importers of products containing PFAS will be required to gather and report the amount of PFAS in their products. EPA’s new PFAS Reporting Rule will produce the largest ever dataset of PFAS-containing products, reaching back to 2011.[1] The Rule covers a vast array of consumer and industrial products, including apparel, furniture, carpeting, fire-fighting foam, and cookware. It also provides no de minimis threshold for reporting on the amount of PFAS that must be present in the material manufactured or imported.

Several states, including Washington, Maine, and Minnesota, have already adopted reporting requirements that impact PFAS-containing products.[2] But EPA’s Reporting Rule is in many ways even broader than these state rules. The rule, which was promulgated under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), uniquely requires reporting that covers the last dozen years. Gathering and submitting historical manufacturing and import information will require a monumental effort, including a review of current and historical documents, and current and former staff members across several departments of the reporting company. It will also require legal consideration of how to protect confidential business information, attorney-client privileged materials, and marketing strategies.

In this two-part series, we will first discuss the deadlines and requirements set out in the new federal rule, which was published in the Federal Register on October 11, 2023.[3] In the second part of the series, we will offer suggestions that businesses may wish to consider in preparing to report to EPA and states alike.

Who is Covered by EPA’s PFAS Reporting Rule?

The new rule may be the first time that many manufacturers and importers of consumer products have had to file reports under TSCA.[4] Even those who have may be surprised by its reach. The rule broadly covers manufacturers of PFAS chemicals as well as consumer product manufacturers and importers of articles containing PFAS.[5] Given the ubiquity of PFAS-containing consumer products—including apparel, food packaging, cookware, carpets, specialty electronics, and even automobiles—the new rule will implicate thousands of products. It will even reach product manufacturers or importers that have phased out PFAS.

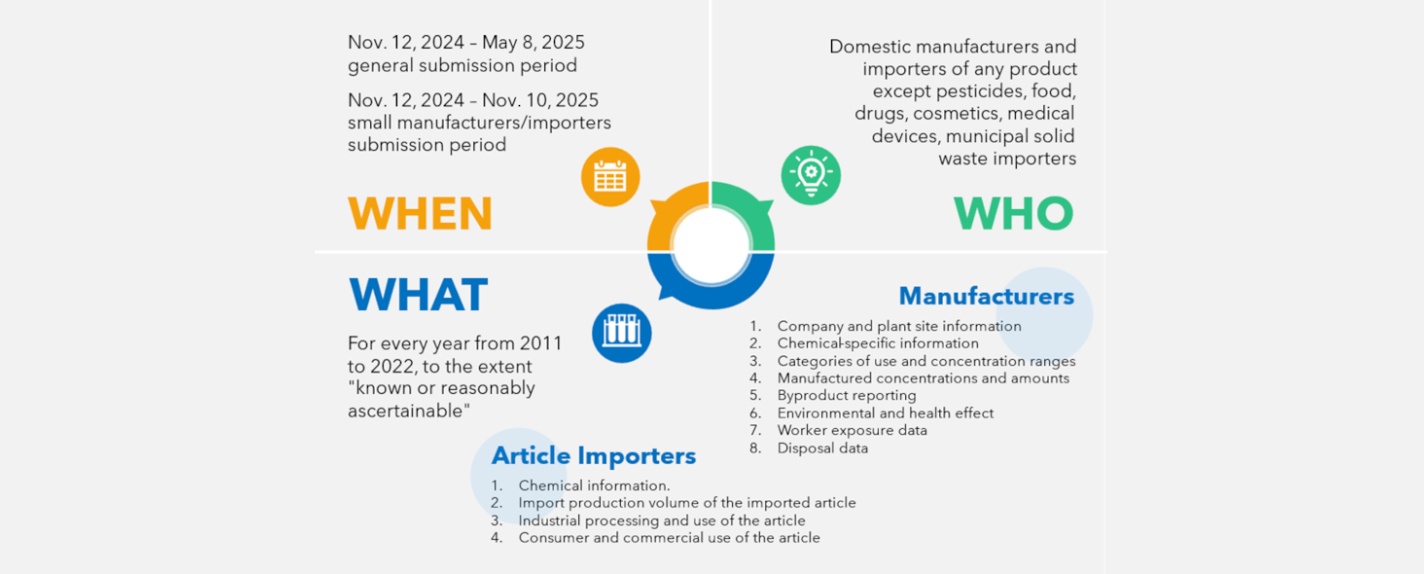

The reporting requirements apply to any company that has manufactured or imported a product containing PFAS between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2022.[6] The final rule provides a few narrow exclusions from reporting, such as when PFAS is produced solely for use as a pesticide, or in food, in food additives, drugs, cosmetics, or medical devices.[7] In addition, the rule excludes PFAS found in municipal waste. There is no small business exemption, however there is delayed reporting for businesses below a certain size.

What Will Businesses Need to Report?

The Rule requires filing detailed reports for the years 2011 to 2022. There is a streamlined reporting form for those businesses that only import articles containing PFAS, which if available slightly decreases a business’s reporting obligations.[8] Otherwise, full reports must include:[9]

- Company and plant site information. Information on each site where a reportable PFAS chemical is manufactured, including information identifying the reporting entity’s highest-level U.S. parent company. The official submitting the information must certify the accuracy of any confidential business information protection request, the name of the technical contact for the reporter, and the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code for the site(s).[10]

- Chemical-specific information. The report must include the PFAS common or trade name, its chemical identity, the Chemical Abstracts (CA) Index Name and the Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number (CASRN) for reportable PFAS. When not available, the generic name or description of the PFAS being reported may be used. Other required information includes the physical form of the PFAS. EPA has established a method for jointly reporting this information for entities that do not know the chemical-specific information but purchase PFAS chemicals from a supplier that would have that information. The joint submission process is described in further detail below.[11]

- Categories of use and concentration ranges. Reporting companies must categorize the use of PFAS for each chemical substance manufactured for commercial purposes based on codes provided by EPA, such as industrial applications (industry specific manufacturing, processing as a reactant, etc.), functional applications (adhesives, sealants, emulsifier, etc.), and consumer and commercial product categories (furniture, textile finishing, packaging, paint, etc.).[12]

- Manufactured concentrations and amounts. Information must be provided on the total volume (in pounds) of PFAS manufactured, imported PFAS volume, each year of the reporting period, and production volumes.[13]

- Byproduct reporting. Companies reporting must identify any byproducts produced through the manufacture, processing, use, or disposal of PFAS at each manufacturing site including the CASRN of the byproduct, a description of how the PFAS manufacturing led to such byproducts, whether those byproducts were released into the environment and by which medium, and the volume of those releases.[14]

- Environmental and health effects. Information must be provided concerning the environmental and health effects of each reported PFAS in the possession or control of the reporting entity.[15] EPA has clarified that this would not require the reporter to search for information “in the public realm” but would rather cover “any data or other information in files maintained by the submitter’s employees” or related entities regardless of its publication status.[16]

- Worker exposure data. The number of individuals exposed to PFAS in the reporting entities’ manufacturing site must be reported, as well as the frequency and duration of the exposure.[17]

- Disposal data. Finally, there must be annual reporting on disposal of PFAS and PFAS-containing products, including the volume of wastes containing PFAS disposed.[18]

Failure to provide reportable information under the rule may expose the reporting entity to civil and criminal penalties under TSCA. Violations could result in penalties that exceed $45,000 per day, per violation.[19]

The details sought under this Reporting Rule raise a number of questions. They include how to search for the required information, including historic information. There is a due diligence standard set by EPA that requires reporting of information that is “known to reasonably ascertainable.”

How Will Businesses Collect and Submit This Information?

Reporting companies will no doubt find that the new reporting rule raises numerous questions about how a product manufacturer or importer is expected to collect and report the detailed information that EPA is requiring by the end of next year. EPA has provided limited guidance on the topic. EPA requires a covered business to supply the requested information to the extent any such information is “known to or reasonably ascertainable.”[20] When actual data are not available, EPA will require a “reasonable estimate.”[21]

The standard of due diligence for PFAS reporting is the same standard EPA uses in its Chemical Data Reporting (CDR) rule. Guidance issued under that program provides that information “[k]nown to or reasonably ascertainable by” the submitter means “all information in a person’s possession or control, plus all information that a reasonable person similarly situated might be expected to possess, control, or know.”[22] EPA expects a “case-by-case” and “complete” analysis in light of the submitter’s “particular circumstances.”[23]

Engaging in this kind of search can be a daunting task, but there are concrete steps that businesses can take as they begin to respond to EPA. They include building a team, making a comprehensive search plan, and documenting each search and conclusions.

Build a Team

Build a team with the knowledge and skills necessary to engage in this search. Appoint a team leader who can coordinate the search. Include a cross-section of business functions that may have knowledge of where to find relevant information—that may include product designers, supply chain relationship managers, marketers, and IT department members. Bring in outside expertise, including legal support, to help engage in this record search as well as to support in the documentation of the search.

Make a Comprehensive Search Plan

This kind of data gathering exercise is not unique in the law—the discovery process provides a useful analogy for how to engage in a thorough information search. Reporters may want to use an information gathering framework, such as the Electronic Discovery Reference Model (EDRM), as a guide to gather and manage reportable information. While frameworks like the EDRM have generally been fashioned to outline stages of document management in a litigation framework, it can be a useful guide for managing any data collection and production exercise.

The EDRM stages include:

- Identification. Consider the different types of records, record custodians, and record locations relevant to this search. Relevant records may exist in both electronically stored information (ESI) and paper copy form, including email memoranda, reports, notes, minutes, drawings, notations on documents, contracts, microfilm, videotapes, and more. Identify custodians who may hold relevant data, including current employees, former employees that have left a digital file universe, as well as external clients who may provide you with access to relevant documents.[24] Finally, create a data map that provides an overview of where data is and how to access it. Data locations may include network or shared drives, cloud spaces, storage media (such as thumb drives, hard drives, and DVDs), databases, work and home computers, and work email accounts (and personal email accounts, if used to share relevant information).

- Collection and Processing. Think about how you are going to collect and stage documents for future determination of their usefulness. This can include storage space considerations, collection method (self-collection by employees or an internal IT department, vendor-led data collection, etc.), searchability of documents (i.e., containers files will need special search accommodations), and data location. If the data resides in archives or a backup space, or is on a deletion schedule, consider placing a hold on deletions while you are in the process of gathering documentation. If the backup data is compressed or otherwise becomes differently formatted in the process of being backed up, consider engaging a forensic specialist to assist with the collection. Decide who will engage in searches, and how information will be shared, collected, and stored.

- Review. Once the documents are collected, you will need to appoint one or more reviewers to determine which records are responsive. Businesses should implement a system that will capture the reviewers’ work by identifying useful documents and setting aside unnecessary data. These reviewers should also be capable of identifying any Confidential Business Information (CBI) that may exist in the records and begin the process of substantiation.

These steps generally accord with examples that EPA provides on how to engage in the search process under the known or reasonably ascertainable due diligence standard. They include, for example: a business that contacts its largest customer to reconstruct missing data on the types of chemicals that their customers have historically purchased;[25] a business researches its largest customer’s website to understand their business practices and the use of products sold to that customer;[26] outreach to an importer’s suppliers to determine the name, CASRN, and molecular structure of the PFAS in their product;[27] other inquiries to first tier or immediate suppliers;[28] and inquiries across the “full scope of [the] organization,” not simply within the ambit of “managerial or supervisory employees.”[29]

Critically, EPA has also provided examples of what is not necessary under the standard. EPA has clarified, for example, that the rule “is not a product testing requirement,”[30] and that reporters should not conduct new customer survey to create new datasets.[31] But those limitations do not prevent a business from making reasonable assumption in its reporting.[32]

Document the Search and Conclusions, and Submit Information

Along with conducting the search itself, businesses should document their search as well as any conclusions reached. That documentation will provide your business with the information needed should EPA, NGOs, or members of the public later question any submitted information. The PFAS Reporting Rule requires that information submitted to EPA be retained for five years,[33] so documentation should also be created to understand how and why data was submitted in the way that it was even years later. EPA recommends that documentation should include the search methods employed in order to document due diligence.[34]

Should the search turn up no information even after pursuing the due diligence standard, EPA requirements allow reporters to instead submit “reasonable estimates” of the required information.[35] If the reporter cannot make such reasonable estimates, they may submit that the information is Not Known or Reasonably Ascertainable (NKRA) in lieu of a requested estimate or range.[36]

With information in hand, EPA has asked for all information to be submitted electronically via the Central Data Exchange (CDX) reporting tool.[37] Be prepared to sign up for CDX, convert any paper data into an electronic format, and submit information accordingly. Consider any document metadata you may be transmitting in your submission to EPA as well—it may contain information you don’t intend to submit.

EPA plans to make portions of the information public so that state and federal agencies may set priorities for regulation and to help consumers avoid specific products. Whether or not EPA makes records public on its own, submissions may become subject to public records requests. EPA expects that the PFAS data it collects could potentially be used by the public, including consumers wishing to know more about the products they purchase, communities with environmental justice concerns, and government agencies to take appropriate steps to reduce potential risk. As a result, your business may consider whether to submit a CBI claim to protect submitted information. In the next article in this series, we will describe that process and considerations that may go into preparing a CBI claim.

What if a Business’s Supplier Controls the Information?

It may be the case that a reporter does not know the chemical content of their product, even if they know (or suspect) that the product contains PFAS. This can particularly be true for article importers. The PFAS Reporting Rule provides an entirely new process for joint reporting where a reporter can identify a relevant supplier that would be better positioned to provide EPA with information on the chemical content of the relevant product.[38] Depending on the results of your due diligence efforts, joint submission may be the best path forward to provide responsive information to the agency. Further, the joint submission process provides avenues for the supplier to submit its own CBI claim regarding chemical information.

What is the Reporting Timeline?

Generally speaking, the timeline for complying with this rule will be about 18 months.

The general submission period will begin one year from November 13, 2023 (the effective date of the rule) and be open for six months—November 12, 2024 to May 8, 2025.[39] Certain “small manufacturers” whose reporting obligations under the rule exclusively concern article imports will, however, receive an additional six months to submit the required data—until November 10, 2025.[40] EPA defines “small manufacturer” in this context as (1) a manufacturer (including importer) whose total annual sales, when combined with those of its parent company, are less than $120 million, and the annual production or import volume of a chemical substance at any individual site controlled by the manufacturer is less than 100,000 pounds; or (2) a manufacturer (including importer) whose total annual sales, when combined with those of its parent company, are less than $12 million, regardless of the quantity of chemical substances produced or imported.[41]

Businesses subject to the rule must also retain records documenting the reported information for a period of at least five years after the end of the submission period.[42]

Conclusion

Given the very short 18-month timeline for gathering the information required to satisfy EPA’s PFAS Reporting Rule, and the various state reporting regimes in play, consumer-product manufacturers and importers will need to begin planning to substantiate CBI protection of their products, gathering reasonably ascertainable data, and assuring the completeness of the data submitted. In the second part of the series, we will offer suggestions that businesses may wish to consider in preparing their reports to EPA and states.

Please contact members of Marten’s Consumer Products Practice, including James Pollack, Victor Xu, Emma Lautanen, and Jessica Ferrell if you have questions regarding compliance with federal and/or state PFAS reporting rules.

The authors would like to thank Erin Herlihy and Marina Goodrich for their contributions to this article.

[1] Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. 70,516, 70,516 (Oct. 11, 2023) (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. pt. 705).

[2] Victor Y. Xu, Minnesota and Washington Blitz PFAS in Products; Maine Backpedals, Marten Law (June 15, 2023), https://www.martenlaw.com/news...; James B. Pollack, PFAS in Consumer Products are Targeted by State Regulators and Class Action Plaintiffs, Marten Law (Jan. 4, 2023), https://www.martenlaw.com/news....

[3] Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. at 70,516.

[4] Victor Xu & James Pollack, What Is in EPA’s Billion Dollar PFAS Reporting Rule?, Marten Law (Dec. 5, 2022), https://www.martenlaw.com/news....

[5] Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. at 70,516.

[6] Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. at 70,516.

[7] 15 U.S.C. § 2602(2).

[8] Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. at 70,555 (to be codified at C.F.R § 705.18). This special reporting provision acknowledges the unique challenges that article importers may face in collecting information. The streamlined report still includes much of the same information described in the full report form, but allows for reporting of volume of the imported articles (by units or weight) rather than an estimation of. It also removes byproduct reporting, environmental and health effects, worker exposure data, and disposal data. Domestic manufacturers are not able to use this short-form reporting framework.

[9] EPA has provided a spreadsheet on the rulemaking docket that provides a detailed accounting of the reporting requirements. See Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, Docket Ref. 15.

[10] Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. at 70,550 (to be codified at C.F.R § 705.15(a))

[11] Id. (to be codified at C.F.R § 705.15(b)).

[12] Id. At 551–53(to be codified at C.F.R § 705.15(c)).

[13] Id. at 553–54 (to be codified at C.F.R § 705.15(d)).

[14] Id. at 70554 (to be codified at C.F.R § 705.15(e)). This reporting requirement may be targeted at incidental creation of PFAS and other chemicals through manufacturing processes, such as those identified in EPA’s examination of PFAS created through the manufacturing of fluorinated packaging. See EPA, EPA Releases Data on Leaching of PFAS in Fluorinated Packaging (Sept. 8, 2022), https://www.epa.gov/pesticides....

[15] Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. at 70,554 (to be codified at C.F.R § 705.15(f)).

[16] Id. at 70,524.

[17] Id. at 70,554 (to be codified at C.F.R § 705.15(g)).

[18] Id. at 70,555 (to be codified at C.F.R § 705.15(h)).

[19] See 15 U.S.C. §§ 2614, 2615(a)(1); 40 C.F.R. § 19.4. The exact penalty would vary based on the adjustment factors above, as well as the “extent” of the violation, which ranges from minor (a potential for a lesser amount of damage to human health or the environment) to major (potential for serious damage to human health or for major damage to the environment. See generally EPA, TSCA Section 5 Enforcement Response Policy (amended July 1, 1993).

[20] Id. at 70,550 (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. § 705.15); see also 15 U.S.C. § 2607(b)(2).

[21] Id. (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. § 705.15).

[22] Id. at 70,549; see also Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. at 70,548 (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. § 705.3).

[23] U.S. EPA, Instructions for Reporting 2020 TSCA Chemical Data Reporting at 4.2 (2020), available athttps://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/documents/instructions_for_reporting_2020_tsca_cdr_2020-11-25.pdf.

[24] Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. 70,516, 70,520 (Oct. 11, 2023); U.S. EPA, Instructions for Reporting PFAS Under TSCA Section 8(a)(7) at 4.2 (2023), https://downloads.regulations.gov/EPA-HQ-OPPT-2020-0549-0270/content.pdf.

[25] Id. at 4.1.

[26] Id.

[27] U.S. EPA, Small Entity Compliance Guidance for the TSCA PFAS Data Call at 12, EPA-705-G-2023-3730 (Sept. 2023) at 12.

[28] EPA, Initial Regulatory Flexibility Analysis and Updated Economic Analysis for TSCA Section 8(a)(7) Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances at 7 (2022).

[29] Id. at 8.

[30] Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. 70,522.

[31] Id. at 70,521.

[32] See id.

[33] See id. at 70,558 (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. § 705.25).

[34] If a reporter has exhausted all search and collection activities, with both internal and external clients, and concludes they have no knowledge of having a relationship with PFAS, EPA has proffered that they “need not report under this rule” but the agency “encourages such an entity to document its activities to provide evidence of due diligence.” Id. at 70,521.

[35] Id.

[36] Id.

[37] Id. at 70,559 (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. § 705.35).

[38] Id. at 70,550 (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. § 705.15).

[39] Id. at 70,557 (to be codified at 40 C.F.R.§ 705.20).

[40] Id. (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. § 705.20).

[41] 40 C.F.R. § 704.3; Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. at 70,557 (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. § 705.20).

[42] Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, 88 Fed. Reg. at 70,558 (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. § 705.25).

PFAS, Newsletter Articles

Authors

Related Services and Industries

Authors

Related Services and Industries

Stay Informed

Sign up for our law and policy newsletter to receive email alerts and in-depth articles on recent developments and cutting-edge debates within our core practice areas.